December 18, 2025

You’ve probably heard the term private credit, even if you’re not totally sure what it means.

Private credit, sometimes referred to as private debt or private lending, is money lent by non-bank lenders, like funds, institutions, or even individuals, directly to borrowers. Those borrowers might be businesses or consumers, and the deals happen entirely outside the traditional banking system. Put simply, it’s borrowing without the bank in the middle.

Why Private Credit Has Everyone’s Attention

Borrowers appreciate private credit because it’s faster, more flexible, and less tied up in red tape than a traditional bank loan. Investors like it because it delivers steady cash flow and the potential for higher returns.

Banks, meanwhile, have tightened their lending thanks to tougher regulations and shifting market conditions. That’s left plenty of borrowers searching for options, and private lenders have stepped right in to meet growing demand.

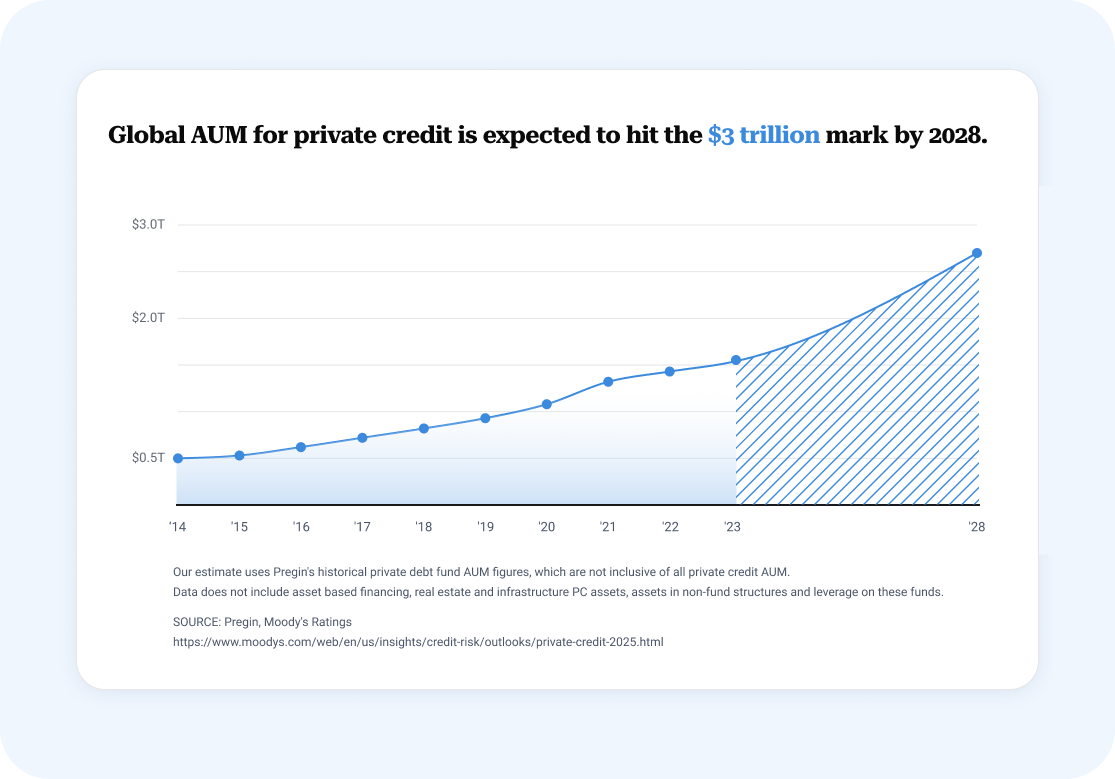

By filling that gap, private credit keeps money moving and businesses growing. Its steady climb is projected to hit three trillion dollars by 2028.

What Recent Private Credit Headlines Got Wrong

With private credit’s rise in popularity, the skeptics were bound to show up.

When auto parts maker First Brands and subprime lender Tricolor filed for bankruptcy, headlines lit up. Comments from JP Morgan’s CEO, Jamie Dimon, about related losses were quickly spun as proof that the entire private credit industry was in trouble. However, a closer look at the facts paints a clearer picture.

The Real Story Behind First Brands

First Brands’ issues didn’t stem from private credit. The company’s main debt came from broadly syndicated loans, structures typically arranged by public banks. On top of that, lenders were hit by the company’s fraudulent use of supply-chain financing.

Here’s where the exposure showed up:

|

Institution |

Reported Exposure/Disclosure |

|

UBS |

Reported losses of over $500 million through a fund in its asset management division. |

|

Jefferies |

Held roughly $715 million in receivables linked to First Brands. |

|

Bank of America |

Confirmed syndicated loans to First Brands, secured by collateral. |

|

Truist Financial |

Disclosed limited exposure during its October 2025 earnings call. |

|

Santander |

Listed about $55 million in exposure through subsidiaries in Mexico and Brazil. |

|

Zions Bancorp |

Recorded a $50 million loss tied to loans connected to the fraud. |

|

Western Alliance |

Reported exposure and filed suit against a borrower over missing collateral. |

|

Morgan Stanley |

Exposed through a fund managed with Jefferies in its asset management unit |

Takeaway: Most of the damage landed with traditional banks, not in private credit.

The Real Story Behind Tricolor

Tricolor’s downfall also had little to do with private credit. The company’s collapse reportedly stemmed from alleged fraud involving “double-pledging” the same collateral for multiple credit lines, a classic case of financial sleight of hand.

Federal prosecutors unsealed indictments on December 16, 2025, alleging fraud on a staggering scale: CEO Daniel Chu and COO David Goodgame are accused of orchestrating a scheme that fabricated $800 million in collateral.

According to charges, Tricolor pledged $2.2 billion to lenders, but only $1.4 billion existed. The charges direct us to what the losses suggested: this was alleged systematic fraud, not a private credit failure.

Here’s where the exposure appeared:

|

Institution |

Reported Exposure/Disclosure |

|

Fifth Third Bancorp |

Reported potential losses of up to $200 million tied to the alleged fraud. |

|

JPMorgan Chase |

Recorded a $170 million loss on loans to Tricolor. |

|

Barclays |

Took a charge of £110 million, roughly $133 million, following the collapse. |

|

Origin Bank |

Disclosed about $30 million in exposure to Tricolor. |

Takeaway: Once again, the biggest hits were absorbed by traditional banks, not private credit lenders.

Putting Private Credit Risk in Perspective

What stands out from the information above is that all the institutions involved were publicly traded banks. That does not mean private market lenders were unaffected, but it shows that the recent bankruptcies were not unique to private credit.

These are some of the largest and most sophisticated banks in the world, built on lending and equipped with advanced underwriting and risk management. Even so, lending is never entirely risk free. Defaults and losses are part of the landscape, no matter how careful the process. In these particular cases, fraud played a significant role, which can challenge even the most diligent lenders.

The takeaway: Private market credit carries risk, just like any other investment. The key for investors is understanding those risks, how they are managed, and whether the potential returns make them worthwhile.